I had the pleasure of interviewing Nihonga artist Nanako Kashiwagi. Enjoy the interview!

Interview with artist, Nanako Kashiwagi

Childhood Struggles: Moving Frequently and Finding Solace in Zoos

Thank you for joining us today. Could you start by telling us a little about your childhood?

Absolutely. As a child, I was really passionate about drawing. From my earliest memories, I was always doodling, creating little sketches whenever I had the chance. I enjoyed playing outside too—tag and the swings with friends from kindergarten—but drawing was what I truly loved. I’d often draw animals, family, and friends.

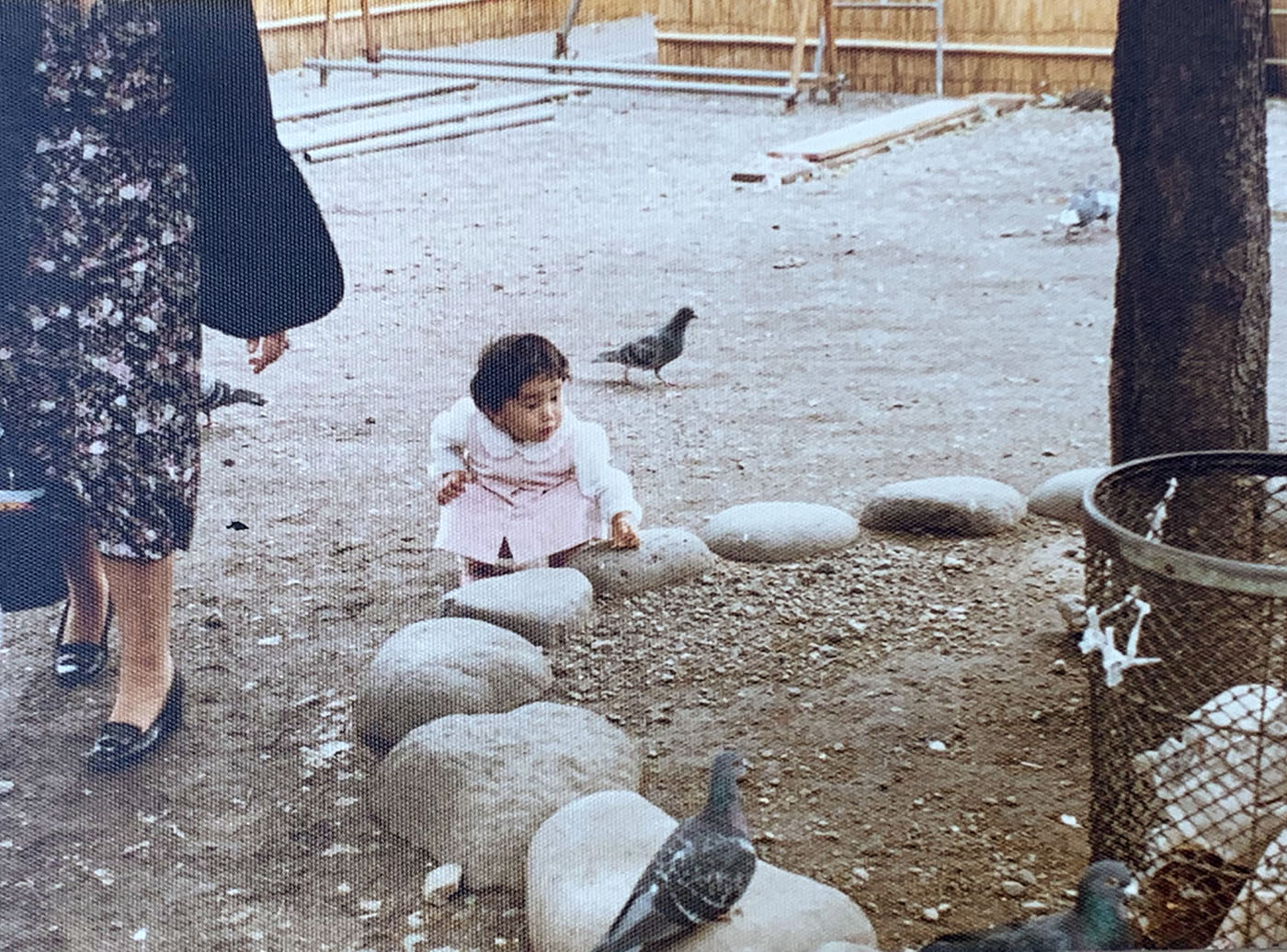

When I was in early elementary school, my parents often took me to the zoo on weekends. It was our go-to outing, about every two or three months. I moved around a lot as a kid, so it was sometimes tough to settle into new places and connect with others. But at the zoo, the animals seemed so at ease, just being themselves without any worry about fitting in. I found their natural, unaffected presence comforting and inspiring.

Do you have any special memories of drawing from your childhood?

Yes, there’s one memory that stands out. I won an award for a drawing I’d done as part of a school assignment, and my art teacher, who always looked out for me, gave me a souvenir from her trip to Singapore as a kind of reward. Knowing that something I was so passionate about meant something to someone else was incredibly uplifting—it made me feel seen and appreciated in a way I hadn’t felt before.

After that, we moved again, and I spent my years from fifth grade of elementary school through third grade of junior high school in Onoda City, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Our company housing was up in the mountains, so I spent most of my time outdoors, exploring and playing with friends. Looking back now, I think it was an amazing environment for a child. But whenever I was home, I’d still be drawing.

Finding Art as a Path to break away from school refusal

What inspired you to pursue art seriously?

When I started high school, we moved back to Chiba, but I didn’t know anyone. It was a bit of a struggle from the beginning—I found it hard to make close friends and was naturally a bit reserved, which made it difficult to fit in. By the second half of my second year, I started feeling overwhelmed and gradually stopped going to school. I spent a lot of time at home, questioning what my future might hold and what I wanted out of life.

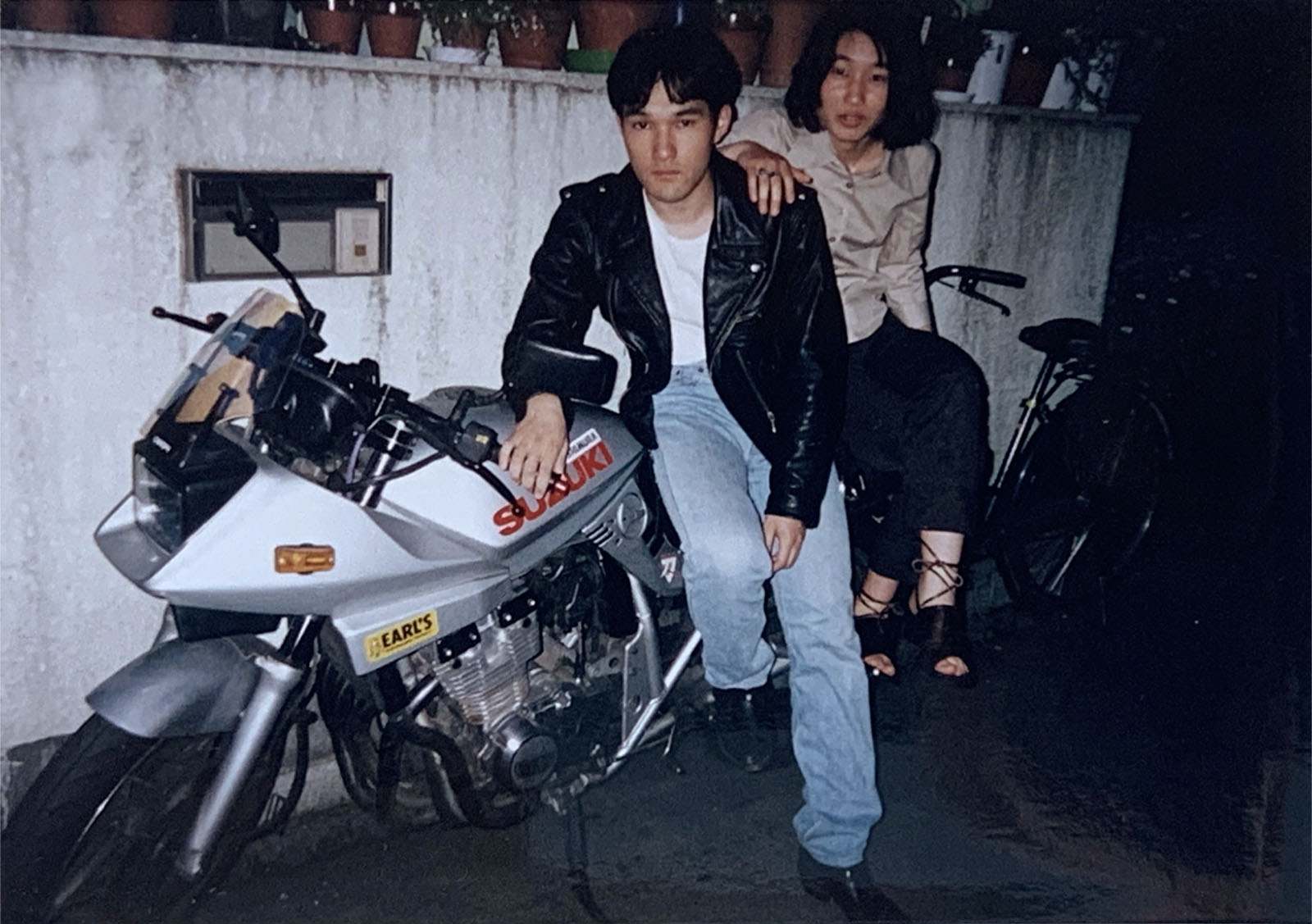

Around that time, my older brother saw how isolated I’d become and took me out for a motorcycle ride, saying, “Let’s go to Edogawa for a bit.” The freedom I felt on that ride, the rush of the wind and being out in the open, gave me a fresh perspective. It made me realize there was a bigger world out there, and I even started becoming interested in motorcycles. I was also attending weekly counseling sessions at a local center, and one day, my counselor asked, “What do you really want to do?” I blurted out, “I’ve loved drawing since I was a kid.” My parents were in stable, traditional careers, so art had never felt like a real option. But that moment made me realize that people actually pursued art as a profession. Once I could envision a future where I might go to art school, I started feeling like I could face school again.

How did your family react when you told them you wanted to pursue art?

My father had often told me to “consider economics for a stable career,” which I had no interest in. I wasn’t sure how my family would react to the idea of me choosing art. I don’t think they had ever imagined I would go down an artistic path, but they could see that pursuing something I truly loved brought a new energy to me. They eventually came around and supported me, which I was really grateful for.

In the summer of my final year, I began attending an art prep school, and it became my motivation—I looked forward to it every day after class. High school still had its challenges, but having art school as a goal helped me stay focused. My teachers were incredibly supportive and understanding, and thanks to their encouragement, I was able to graduate without any issues.

Unexpected Moving to Fukuoka After Marriage

So that’s how it happened! Could you share more about your art studies, your interests during your student years, and what you pursued after graduation?

I studied Nihonga at Tsukuba University, immersing myself in drawing and painting every day. In my first year, several classmates decided to get their motorcycle licenses, and I decided to join them. We enjoyed going on tours together. After graduation, I initially took a job at a design firm, but it was an intense environment, and I left fairly quickly. Living with my parents at the time, I followed their advice and took the civil service exam. I passed and started working, but I ended up leaving after about a year and a half. I thought I could balance a regular job with my painting, but it turned out to be quite challenging. I constantly found myself preoccupied with work issues, which made it difficult to focus on my art. My husband understood my desire to pursue graduate school and that office work wasn’t the right fit for me, so he encouraged me to leave my job.

That led me to take the entrance exam for graduate school, where I was accepted, and I resigned from my job. Around that same time, we got married, but the challenges of a long-distance relationship made it tough, and I ultimately left school after six months to join him. After that, I often sketched at a nearby park, the Odawara Castle grounds.

Did you move to Fukuoka after that?

Yes. My husband applied for a position at a company based in Tokyo, but when he joined, they assigned him to Fukuoka. Following the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, many companies began looking to decentralize. Fukuoka is often praised for its livability, and I’ve found that to be true. However, the sudden relocation made me feel a bit nervous because I had been established connections to be able to continue my art in Tokyo and surrounding area.

How did you manage to keep up with your work as an artist after the move?

Shortly after our relocation, I was out riding my motorcycle when I spotted a poster for an art competition hosted by a historic hot spring in Saga Prefecture. I decided to submit an entry and ended up winning an award. Gradually, I built connections by spreading the word about my work, meeting other artists at exhibitions, and forming relationships with gallery owners who expressed interest. Over time, I found a way to balance my art with raising my children in Fukuoka.

Desperately pained while raising my children, which led to alopecia areata. Now they support and encourage me.

Many artists struggle to balance family responsibilities with their art. How has that been for you?

In the beginning, balancing the demands of a newborn with painting was incredibly challenging. Babies have their own schedules, waking up at all hours, so I would often stay up late, painting during those short windows between feedings. I felt a strong need to keep pushing forward, fearing I would lose my artistic momentum. As my child grew a bit older, I grappled with the pull between cherishing those fleeting moments of childhood and committing to my art. There were times I worried that both might suffer—that I was neglecting my child or my work. It was a difficult period.

Looking back now, I’m grateful for that time, as it shaped who I am today. However, I sometimes wish I could have been kinder to myself, as that intensity led to a health scare; I even developed a patch of alopecia. Still, I have no regrets. My daughter, now a teenager, understands and supports my dedication to painting.

I still manage to get through each day balancing housework and raising my daughter,somehow making it work. But doing what I love has been a source of comfort. Art saved me when I was going through a period of not attending school, and later, it was a lifeline that allowed me to transition from a job I struggled with to a career in painting. When you’re passionate about something, it truly becomes the core of your life. I’ve continued to paint with a lingering sense of attachment, and now my daughter is my biggest supporter. I believe that when a mother is dedicated to pursuing something she loves, that spirit eventually reaches her children. My own mother has always worked, and while there were times, I felt lonely because of it, I now deeply respect her commitment. Even now, I’m able to keep going thanks to the support of those around me, and I’m genuinely grateful to everyone who encourages me.

Have you encountered any slumps during your artistic journey?

Yes, I recently faced one. Around my mid-40s, I experienced a period of low motivation, questioning how I wanted to approach my painting. I had the time to focus on my art with my child becoming more independent, but I found myself lacking the same intensity I once had.

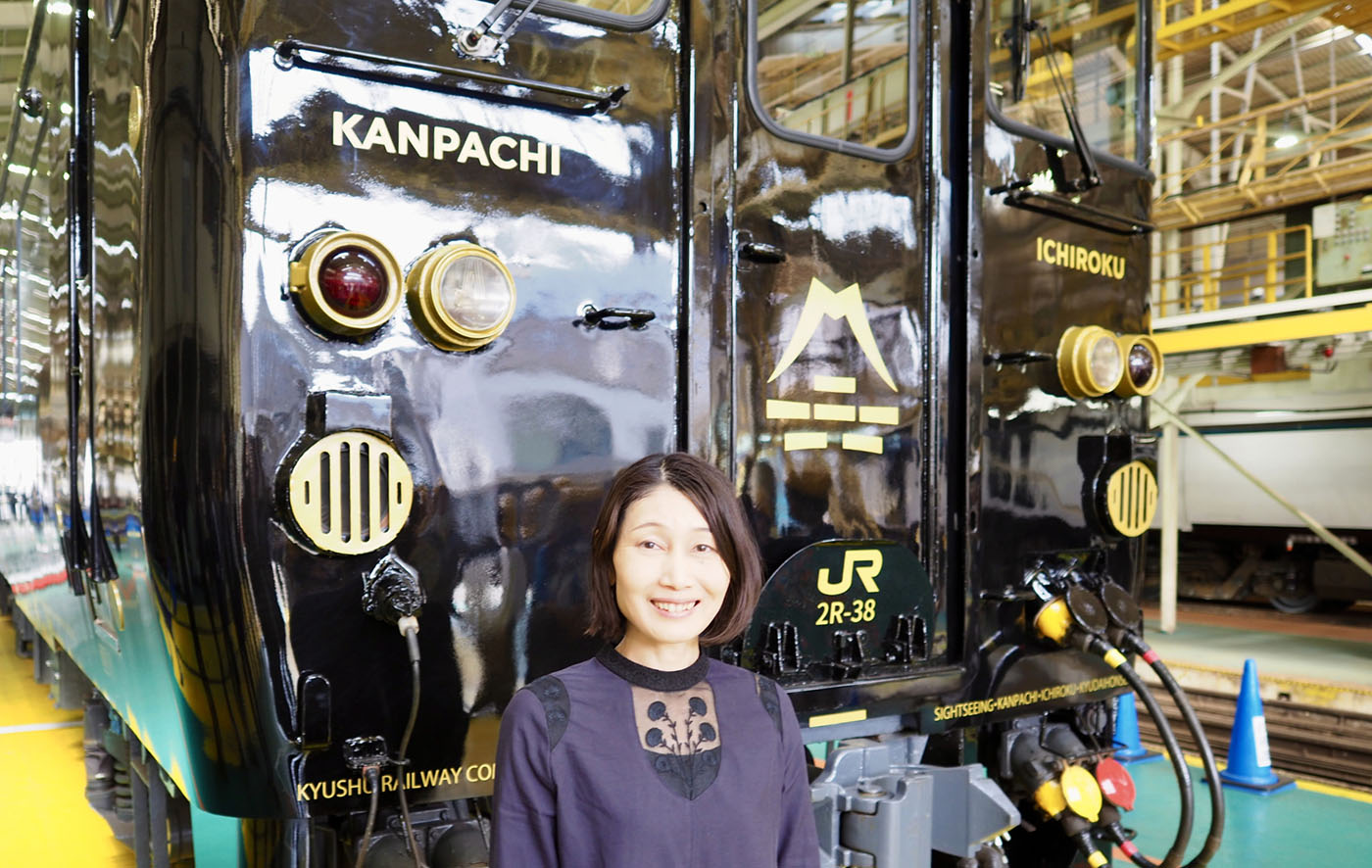

Then, this spring, I received a wonderful opportunity to create artwork for JR Kyushu’s “Kanpachi-Ichiroku” tourist train. It’s a regional project celebrating Kyushu, and through it, I rediscovered the joy of painting and felt a profound connection to this place. This experience reignited my artistic drive and renewed my sense of purpose in being here.

Love for what is lost

By the way, I’ve heard you started riding motorcycles during your student days. Do you still ride?

Yes, I still ride alone sometimes, and I also go on tours with my husband. Occasionally, our daughter rides on the back of my husband’s bike, and we enjoy family tours together.

I imagine there’s quite a contrast between the thrill of riding a motorcycle and the quiet concentration required for Nihonga. How do you reconcile those two experiences in your mind?

I get told that a lot (laugh). It’s true that painting Japanese art demands intense focus and often involves being indoors for long periods, while motorcycle riding is all about being out in the open. However, I find that riding actually brings me a sense of calm. The deep concentration I experience while painting and the solitude I feel while riding my motorcycle through tranquil mountain areas often evoke surprisingly similar emotions. I think it reflects my personality quite well.

I’ve heard that your interest in ruins developed while you were touring. Can you share what specifically sparked that interest?

It all began in 2010 when I visited Atami. I encountered an abandoned hotel that had fallen into ruin, and it was something I had never seen before. I sketched it and used that as a subject for an exhibition. At that moment, I realized that such places could serve as compelling subjects for my artwork.

What is the appeal of ruins?

I find myself captivated by the remnants of past times that are invisible to us now, yet undeniably existed, as well as the quiet presence of weathered ruins. My affection lies in my deep feelings for “what has ceased to exist.” When buildings constructed by humans fall out of use, they gradually integrate with nature over vast expanses of time. My initial encounter with ruins in Atami ignited a strong desire within me to depict them through my art. After moving unexpectedly to Kyushu in 2015, a region rich with ruinous subjects, that desire only grew stronger.

When I first moved here, I immediately thought, “I must visit Gunkan Jima in Nagasaki.” I set out right away. During a guided tour with limited time, I eagerly sketched and photographed the surroundings, which later informed my paintings. Since arriving in Kyushu, I’ve discovered numerous unnamed ruins scattered throughout the area, and I make it a point to visit and sketch these sites. Beyond Gunkan Jima, I’ve explored the expansive fan-shaped locomotive shed and turntable at Bungo Mori Locomotive Park in Oita, as well as the remains of the Eino Island coal mine by my car. While this may be a slight digression, many ruins also serve as war heritage sites, and learning about them can be quite painful and difficult. However, I also find meaning in these places that are no longer in use, and I feel a sense of profound emotion about them.

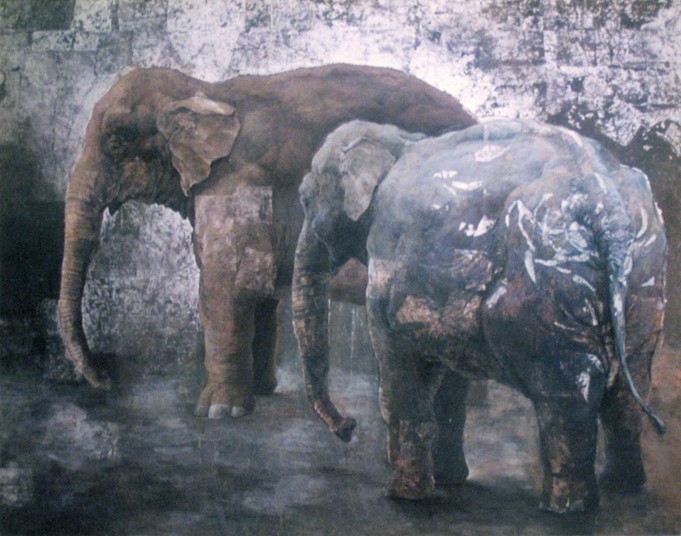

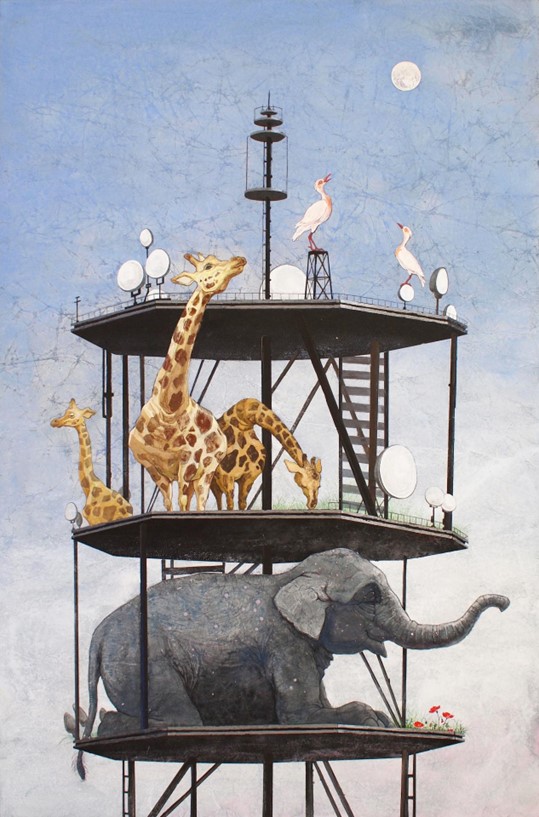

What inspires you to depict animals within these spaces?

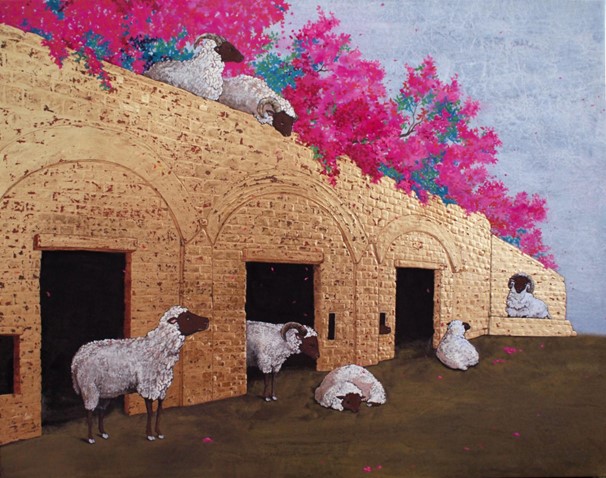

When I paint animals, I see them as both present beings and echoes of the past. There’s a tenderness in capturing creatures as they are, similar to ruins, which reflect life’s impermanence.

Once, I encountered a painting of Noah’s Ark that featured a mythical creature called a Nue. It taught me that you don’t have to paint only what you see. That inspired me to paint a dodo, an extinct bird I’ve always found endearing.

Additionally, having moved frequently during my childhood and struggling to fit in, I became drawn to the natural behaviors of animals after I started visiting zoos more regularly. Animals seem to exist without worrying about fitting in with their surroundings, even placed in a ruin, they would still behave as they naturally would, I imagine.

In front of ruins that people often overlook, I paint animals, which are beings that will one day cease to exist, to highlight the beauty of ‘being alive now.’ Through my art, I transform the affection I feel for both ruins and animals into a message for people who are desperately living in the present.

I eagerly await to see the works you will create in the future.

Thank you so much for today.

(Interviewed and written by Ichinose Imoko)

Postscript on creation: Nanako Kashiwagi, Nihonga art ‘Kazamidori’

Nanako Kashiwagi

Japanese painting, size F6 (410 x 318 mm)

Postscript on creation: Nanako, Nihonga art ‘Kazamidori’

After giving birth to my daughter and building a house in Kanagawa, I thought I was finally settling into a calm and stable life. But just as things were coming together, my husband’s career change required us to move suddenly to Fukuoka. We had to part with the custom-built home in my birthplace of Kanto district, and I found myself in a completely unfamiliar place, navigating both the uncertainties of raising a child and the unpredictable path of my work as an artist.

Still, I thought, “Since we’re in Kyushu, we might as well make the most of it.” One of my long-held dreams was to visit Gunkanjima, so I immediately signed up for a guided tour and was lucky enough to make the trip (at the time, my daughter was still very young, and there was only one tour company that allowed children her age. Landing conditions were also highly weather-dependent, so the opportunity felt like a rare stroke of fortune). My painting Weathercock is based on the sketches I made during that visit.

The scenery on Gunkanjima was breathtaking, unlike anything I had ever experienced before, and I became completely engrossed in sketching. Even the decaying concrete ruins carried a haunting beauty. I’ve always loved animals, and when I thought about what I wanted to portray, I chose an owl?a creature that symbolizes foresight and wisdom?as my subject.

The Japanese word kazamidori (weathercock) often carries a negative connotation of being indecisive or swayed by circumstances. But in creating this work, I used the kanji for bird to evoke a living creature and infused the piece with a different meaning: the idea of catching the winds of the moment and using them to move forward with intention and purpose. This painting expresses my wish to remain true to myself, no matter where life takes me or how unexpected the circumstances. At the same time, I hope that those who view this piece will feel inspired to make the winds of their current situation their own.

May favorable winds always guide your journey.

( Nanako Kashiwagi )

Nanako Kashiwagi, Artist bio

1977 Born in Chiba Prefecture

2000 Graduated from University of Tsukuba

2000 Graduated from the Japanese Painting Course, Department of Fine Arts, University of Tsukuba

2005 Selected for the Garyu Cherry Blossom Japanese Painting Grand Prize Exhibition (’06,’09)

2012 Second Prize, ART BOX Grand Prize Exhibition

2015 Selected for the Art Newcomer Award “Debut 2015

2016 Selected for the Seed Yamatane Museum of Art Japanese Painting Award

Solo Exhibitions

2006 Solo Exhibition at Kanagawa (’08)

2009 Solo Exhibition at Kanagawa (’10)

2016 Solo Exhibition in Fukuoka (’19,’20,’22,’24)

2017 Solo Exhibition / Kanagawa, Japan

2018 Solo Exhibition in Tokyo

And many more